|

NOLSW/UAW Local 2320, 30 YEARS A VOICE FOR JUSTICE

The history of NOLSW is a part of the history of the American anti-poverty movement, shaped by the vision of its founders and succeeding generations of members and the extraordinary support of the UAW.

BEGINNINGS

NOLSW is now a union of “justice workers” of all kinds, from LSC and non-LSC funded programs for the poor, human services agencies, protection and advocacy programs serving people with disabilities, labor law firms and union legal services funds, legal defense and education funds, constitutional rights defenders and more. But the roots of our Union are in the anti-poverty law movement of the sixties and seventies.

Prior to that time, legal assistance to the poor was the domain of settlement houses and legal aid societies. Settlement houses were created to provide social services to immigrant workers in the nineteenth century—including Chicago’s famed Hull House, whose workers are members of NOLSW. Legal aid societies were charitably funded organizations that generally stuck to legal advice, under pressure from an organized bar protecting its monopoly in the courts.

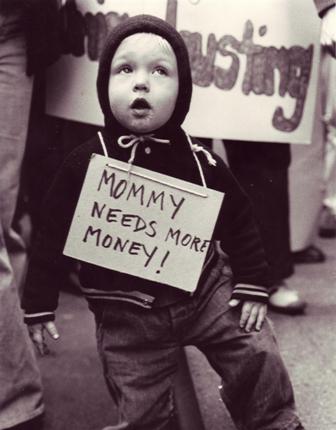

<!--[if !vml]-->  The sixties saw the advent of the modern social work profession, with its focus on treating the sources of poverty; and the civil rights movement’s success using litigation to produce systemic change. In 1964, Lyndon Johnson launched the “War on Poverty” that included the creation of local, federally-funded Community Action Programs designed to fight poverty through community organizing. In 1966, anti-poverty advocates persuaded Johnson to add funding for legal services, and within a year, hundreds of programs sprung up around the country dedicated to using the legal system to fight poverty. The sixties saw the advent of the modern social work profession, with its focus on treating the sources of poverty; and the civil rights movement’s success using litigation to produce systemic change. In 1964, Lyndon Johnson launched the “War on Poverty” that included the creation of local, federally-funded Community Action Programs designed to fight poverty through community organizing. In 1966, anti-poverty advocates persuaded Johnson to add funding for legal services, and within a year, hundreds of programs sprung up around the country dedicated to using the legal system to fight poverty.

The early legal services advocates, who worked in “neighborhood” offices and “think-tank”-like organizations like the Center for Welfare Rights, rejected the ineffectual legal aid model. Instead, collaborating with community organizers and civil rights activists, they helped build client organizations and used strategically planned litigation and legislative advocacy to pursue social and economic reform. In the decade that followed, an amazing 164 cases brought by legal services lawyers reached the Supreme Court, leading to the establishment of important statutory and constitutional rights that we take for granted today.

By the early 1970s, however, challenges to entrenched political interests produced a backlash, led by agribusiness intent on crushing the activism of rural legal services programs on behalf of farm workers. The result, during the Nixon Administration, was the creation of the Legal Services Corporation. While it extended federal funding for legal services to cover every state and county, the LSC Act also placed programs under the control of boards controlled by local bar associations and brought the first stringent restrictions on the types of cases that could be brought and clients who could be represented.

In addition to this unprecedented interference with their professional independence, legal services workers had other concerns, such as abysmal pay, arbitrary firings, discrimination, and poor office conditions. Perhaps inevitably for such a feisty community, they began to organize to seek for themselves the just working conditions necessary to best serve the needs of their clients. In many programs around the country, legal services workers concluded that, in order to effectively address these issues, they needed to have collective bargaining rights, and independent unions soon formed in New York City, New Jersey, Detroit, rural California, and Texas among other places.

As informal national networks developed, legal services workers began to discover that these concerns were widely shared. Regional meetings were organized. With no resources to speak of, these meetings were run on a shoe-string. People were put up on living room couches. Workers from around the country contributed to a fund and disbursements were made to cover the expenses of traveling delegates, creating a sense of collective responsibility.

<!--[if !vml]-->  <!--[endif]--> In June, 1977, some one hundred and twenty legal services workers from around the country gathered in New York City, including representatives from nine of fifteen programs that were already unionized. The conferees adopted “principles of unity” for a fledgling association dubbed the “National Organization of Legal Services Workers”, including:

-

-

-

-

- Publicly-funded legal services for the poor is a fundamental right;

- Unionization of local legal services programs is needed to strengthen and unify staff and client groups to fight for better working conditions and service delivery;

- The organization of all staff within each local union is essential;

- A national organization is necessary to promote the interests of staff and clients; and

- NOLSW opposes racism, sexism and elitism in pursuit of these goals.

In June, 1978, NOLSW held its founding convention in Detroit, with delegates from thirty states and nearly 30 independent unions, an ethnically and racially diverse group representing programs large and small and urban and rural, and every job category. The convention adopted a constitution and elected Bronx Legal Services lawyer Jim Braude as its first President. The Convention also elected Marcos Lopez, a paralegal from Texas Rural Legal Aid, as National Vice-President and Regina Little, an attorney from Middlesex County, New Jersey as Treasurer.

By its third national gathering in the summer of 1979, NOLSW had grown to fifty local unions, many in need of help organizing, negotiating contracts, and combating anti-union employer campaigns. As the delegates met, the Legal Services Staff Association (LSSA) in New York City was in the midst of an eleven week strike. Although LSSA had generated considerable support, it was clear that without the resources of a larger union, it would be difficult for any local union to win a protracted struggle.

At the same time, thousands of legal services workers remained to be organized. NOLSW needed expanded resources to continue the momentum. Delegates also felt it increasingly urgent that they have an organized national voice as Congress began considering massive cuts to the LSC budget, amendments to prohibit strikes by legal services workers, and to place crippling limits on the kinds of cases that programs could pursue. In response to all of these concerns, delegates created a committee to investigate affiliation with a larger, national union.

Six months later, the committee recommended affiliation with District 65, an established, progressive union that also represented New York City’s public defenders, and was itself about to affiliate with the United Auto Workers. NOLSW’s affiliation with District 65 enabled it to remain a national union, but allowed it also to access the national resources of the UAW. Equally important to NOLSW was the UAW’s long history of support for progressive social causes, including the creation of federal, anti-poverty programs. In fact, the legislative director of the UAW at the time, Dick Warden, had been personally involved in the creation of LSC.

On August 15, 1980, in Madison, Wisconsin, NOLSW delegates voted overwhelmingly to adopt the committee’s recommendation. Twelve years later, District 65 was fully merged into the UAW and ceased to exist as a separate entity. Mindful of the continuing need for a strong national entity advocating for the legal services program and its workers, NOLSW negotiated with the UAW to keep its unique structure. Thus, in 1992, NOLSW was chartered as UAW Local 2320, becoming the UAW’s only “national amalgamated local.”

STRUGGLES

In one of its earliest victories, NOLSW rallied to stop a politically-motivated LSC investigation of Northern Mississippi Rural Legal Services (NMRLS) instigated by a congressional aid named Trent Lott at the behest of local Klansmen who opposed an African-American community group represented by NMRLS. Aided by staff attorney Lew Myers, the group had angered the Klan by conducting a boycott of Tupelo businesses and leading mass marches. NOLSW members traveled to Tupelo to march and were confronted by gun-wielding Klansmen (many of whom were local police officers). NOLSW later held a MLK day protest outside LSC headquarters in Washington. LSC ultimately cleared NMRLS and Myers.<!--[endif]-->

However, never was the need for a national organization backed by a powerful national union more clear than in 1981when President Reagan announced his intent to abolish legal services. Reagan came into office obsessed with destroying legal services because of persistent litigation against his programs as governor brought by California Rural Legal Assistance. The American Enterprise Institute drafted a transition paper for the Reagan Administration specifically devoted to the abolition of legal services. Reagan was backed in this goal by powerful industry groups like the American Farm Bureau and its huge political action committee, a major contributor to legislators all over the country.

<!--[if !vml]-->  <!--[endif]-->

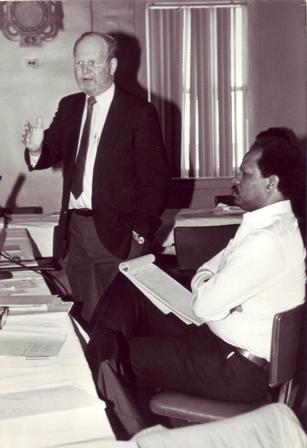

Despite the fact that NOLSW had only recently affiliated with the District 65 and had not yet begun to pay dues, the UAW immediately threw itself into the fight. NOLSW President Jim Braude was invited to address the UAW’s political “field army” at its annual Community Action Program (CAP) conference.

A CAP subcommittee was created devoted to saving legal services and the issue was placed at the top of the political agenda of more than 1,000 delegates who went to Capitol Hill to lobby. Dick Warden, the UAW’s Legislative Director and chief lobbyist opened doors for NOLSW members to present their case to some of the most influential members of Congress.

Backed by this support and an enormous grassroots effort by local NOLSW units, Reagan’s plan was defeated and thereafter, he turned to destroying the program from within by the appointment of conservative LSC boards. In 1998, at the prompting of LSC Board members and staff, Representatives Bill McCollum (R-FLA) and Charles Stenholm (D-TX) introduced an amendment to the appropriations bill that sought to attach severe restrictions to LSC funding. The amendment was introduced just two days before the vote on the entire appropriations bill and came as a total surprise to the legal services community. Backed by this support and an enormous grassroots effort by local NOLSW units, Reagan’s plan was defeated and thereafter, he turned to destroying the program from within by the appointment of conservative LSC boards. In 1998, at the prompting of LSC Board members and staff, Representatives Bill McCollum (R-FLA) and Charles Stenholm (D-TX) introduced an amendment to the appropriations bill that sought to attach severe restrictions to LSC funding. The amendment was introduced just two days before the vote on the entire appropriations bill and came as a total surprise to the legal services community.

Under the leadership of then President Dwight Loines and Treasurer Joe Mesar, NOLSW organized a massive lobbying effort, involving members from all over the country. More than twenty members from the New York metropolitan area responded to an emergency summons and set out by Amtrak the following morning to Washington DC, gathering together in a single car to be trained on lobbying and develop talking points. Later that day, the Stenholm-McCollum amendment was narrowly defeated on the House floor.

The struggle marked a turning point for NOLSW in its relationship with program management, LSC and the ABA, who saw the critical role that unionized legal services workers could play in protecting legal services. Indeed, NLADA honored Dick Warden for his role in killing the McCollum-Stenholm amendments. With no time left on the clock, and the “yeas” holding a slim majority, Dick Warden convinced three Democratic representatives to change their “yes” votes to “no.”

<!--[if !vml]-->  <!--[endif]--> Throughout the Reagan and the first Bush years, legal services remained on the defensive. LSC’s authorization expired in 1981 and again and again, with the UAW’s help, efforts to kill legal services were defeated. There was never a real hope of renewing LSC’s authorizing legislation, however, until President Clinton was elected. With Representative Barney Frank (D-MA) chairing the House subcommittee responsible for authorization, NOLSW began lobbying not only on reauthorization, but a national pension program for legal services workers and a Union seat on the LSC Board!

Once again, Dwight and Joe organized a nation-wide lobbying effort around reauthorization. Armed with a decade’s worth of voting records of House members on LSC issues researched and compiled by outstanding NOLSW staffer, Gordon Deane, and the ever present assistance of Dick Warden, NOLSW orchestrated a sophisticated lobbying strategy that targeted specific House members on each authorization issue. As the bill came closer to a vote, NOLSW met with then Majority Whip David Bonior (D-MI) and the Union was able to give him better vote counts than his own staff.

The legislation was passed by the House in the summer of 1991, after two days of nearly continuous debate and 18 separate votes on specific restrictions proposed by opponents of LSC. Unfortunately, a companion bill never got out of committee in the Senate, as key Democrats focused on President Clinton’s national health care reform throughout most of 1992. All hopes were subsequently dashed when the Democrats lost control of Congress that fall. Legal Services’ traditional adversaries re-emerged and with little support from the White House or the ABA, the Gingrich-led Congress was finally able to adopt the McCollum-Stenholm restrictions.

Throughout this period, Dwight and Joe recognized that the Union was engaged in a national struggle and that it was necessary to continue to build NOLSW to build support within organized labor and win the struggle for federal funding. In the decade preceding Joe Mesar’s unexpected and untimely death in 1998, he and Dwight organized more than 1,000 new workers, including such diverse programs as Georgia Legal Services, Northern Mississippi Rural Legal Services, the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, NARAL Pro-Choice America, the Food Research and Action Center, Miami Legal Services, Travelers’ Immigrant Aid in Chicago, and Oregon Legal Services.

During its third decade, NOLSW has continued to grow and flourish. Ellen Wallace, an attorney from Greater Boston Legal Services, was first elected Financial Secretary-Treasurer to replace Joe Mesar, and then assumed the presidency when Dwight left to become the Political Director for Region 9A of the UAW. A talented and energetic leader, Ellen has continued the tradition of her predecessors, maintaining strong bonds between the UAW’s legislative office and the UAW’s regional and national leadership and the grassroots NOLSW membership. With her leadership, the work of the UAW legislative office led by Alan Reuther, Director and Barbara Somson, Deputy Director, has been closely coordinated with efforts by NOLSW members around the country, to help deliver the first increases in LSC funding in years.

THE FUTURE

NOLSW’s founding members were there at the historical moment when legal services was radically transformed, from a collection of charity-dependent, ineffectual local legal aid programs to a publicly-funded national network dedicated to empowering poor people, defeating the causes of poverty and creating a just society. Their passion and vision produced enormous positive changes but unleashed the lasting enmity of those vested interests whose power they were challenging. They had the wisdom to understand that to sustain the struggle for equal justice, they needed to to act collectively to create just working conditions locally, to unite nationally and to align with the most progressive organized voice for working people, the UAW.

In the ensuing years, legal services has been under continuous assault by the forces of economic and political conservatism. Because of the tenacity and commitment of our members and the unflagging support of the UAW, NOLSW has led the fight to defend the independence of the publicly-funded poverty law network and to advance the interests of our clients in spite of constant adversity. Although our foes ultimately succeeded in imposing devastating restrictions on LSC grantees, like a river finding its course, anti-poverty advocates have always found a way around such obstructions. Programs funded with "unrestricted" state and local funds and other organizations dedicated to the fight for social and economic justice have proliferated to do the work  that LSC programs cannot do. <!--[if !vml]--><!--[endif]--> that LSC programs cannot do. <!--[if !vml]--><!--[endif]-->

Likewise, NOLSW itself has broadened to bring these justice workers into our Union. We have expanded to include workers in many non-profit, public interest organizations and now represent over thirty-six hundred members and one hundred bargaining units. By continuing to build our Union, we build the strength of organized labor, which in turn continues to be the single most important force in electing political leaders dedicated to just policies and which (to paraphrase Martin Luther King, Jr.) is the first and the best anti-poverty program this country has known. Sadly, we still have much to accomplish in a national climate that has grown steadily more hostile to unions.

NOLSW remains committed to its original mission to sustain and build the legal services movement by organizing strong local legal services unions, and to the broader mission of ensuring decent wages and work conditions, workplace democracy and fairness for those whose life work is to advocate for others. After years of struggle, the events of the past year with the changing of control in Congress and the first substantial LSC funding increases in more than a decade we may finally be turning a corner. We have immense pride in our first thirty years and boundless optimism about what we can achieve in the years to come. Unquestionably, together we are stronger than those who oppose us.

|